[DISPATCH] 40 Cities, 40 Nights

notes from my first week back in America — or, celebrating freedom with 1,500 miles on the highway

I’ve been on the run since Wednesday. Not our most recent, but the one before. Likely, even before. Can’t really tell. Time has collapsed on itself as I step into an ecosystem so fragile and small that the rest of the world has no choice but to kneel in submission, yield importance. Come along for the ride.

Bogotá, Distrito Capital, Colombia (Thursday)

After enduring three years of constant psychological warfare at the hands of Peace Corps’ outlandishly abusive and imperialist program, my sentence has come to an end.

In my last days as a civil doormat, I felt a turbulence of emotion. My last day, gliding down the steps felt like first rain as a free man. To the wind, I screamed: “I can ride a horse! I can jump on a motorcycle! I can do blow!” Over tequila and tres leches, I sobbed and scolded in equal measure. I felt an inherent fragility, vulnerable like porcelain. I also felt an invincibility, newly untraceable therefore untouchable. I assume this dynamism is what the cards warned me of last December. Changes in sentiment as uncertain, as unpredictable as the change of seasons — powers that be always ensuring a pendulum’s return to equilibrium.

I spent my last month in Colombia outside. Which is to say I left the same way I arrived: stumbling around in the wee hours of the morning with a handle, singing “Defying Gravity,” trying to screenshot the moment because I never wanted to forget it. Even as I dutifully attended every asado, baby shower, lunch, birthday party, and coffee date, I mourned. Time escaped. More and more, I couldn’t find time to say goodbye. Though I have left many places and many people, I’ve never been more desperate than I was in those final days. I had to rip up roots again.

Repeatedly, whenever I apologetically declined an invitation, I recieved, “Ay, no me digas. ¿En verdad? Pues, bueno. ¿Oye pero cuándo te vas? Ay no ... que mal, Leti. Tabio va a extrañarte mucho. ¿Pero cuándo regresas?”

This stumped me. Public opinion assumed I would return. Even still, sooner rather than later. Well, why wouldn’t I?

In the same vein Peace Corps enabled a feeling of true desperation, living in Tabio helped me experience divine alignment.

Even though my time in Colombia seemed like a complete 180 from the career I studied and trained for, I spent the past year living in my element. At work, I’d alternate between five campuses in three separate municipalities, teaching classes and facilitating workshops on civic responsibility and identity formation. In my free time, I’d entertain or be entertained by the masses. Confident and capable, I considered life actualized. Finally, everything I had ever endured or put up with felt worth it. A new future — whole and bright — revealed itself to me.

But it all had to end.

My reluctance was evident. Every day, I’d wake with a plot in mind, and not a single item on my daily to-do would concern planning and executing a cross-continental move. I lived in Colombia, and I had a life in Colombia. Though I could see myself living in the United States, I didn’t imagine having a life there.

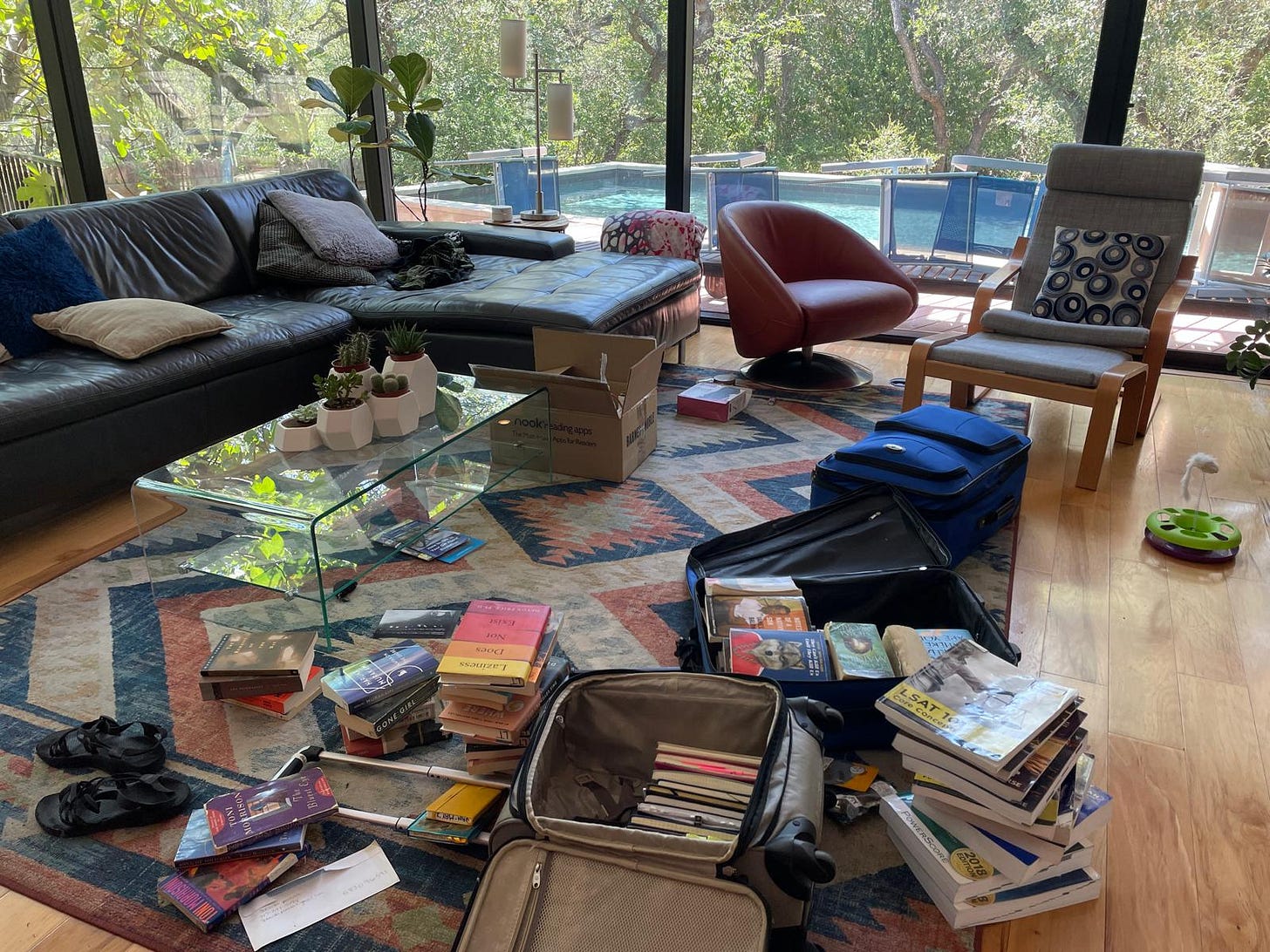

The only thing to soften truth’s bristles was a stateside deadline: I needed to get all my shit out of a storage unit in Chicago and drive it down to Texas before the first Friday of September.

When I signed on to become a government operative, I still lived at the Thorndale estate with Team Gaby. Wanting foresight and time, I never considered an eventuality in my decision. I first attempted to rectify this mistake on special leave — the government-mandated month of American reassimilation all Peace Corps volunteers take before extending service past the standard 27 months — last September.

That time, I walked nearly 10 miles, laser-focused on my bike. Drenched and faint, I gave up on my mission immediately when I arrived at the storage unit and laid eyes on everything I owned. The sheer quantity loomed in front of me. I had committed the ultimate sin of once-impoverished, roof-insecure peoples: having material possessions in our dsyfunctional world. Appalling!

This grand plan to clean out my storage unit, thwarted due solely to negligence. I dropped a thousand at Cubesmart, and I had flown into Chicago for no reason.1 Worse, I would be empty handed on an 18-hour cross-country road trip. Frustration made me stupid, and I threw all caution to the wind on the ride home.

Still, glad that I didn’t have to rent a UHaul, I mentally prepared myself for the journey ahead. Awful for every reason imaginable,2 I vowed when the time to move came again — the real thing! — I would not suffer.

So I did my research.

Rich in information, I decided on a four-night, four-city adventure. Wisely, I waited until the end of Mercury retrograde to finalize details. First, I rented a passenger van. Then, I hired movers in both locations — load in Chicago, unload in Austin. Finally, most important: hotels. I spent days geographically triangulating cheap options and cross-referencing them with BringFido.com to ensure George’s welcome. When the day arrived, a Wednesday of course, I spammed charges to my credit card.

Before I could get a handle on life, my last week in Colombia arrived.

Lulú and I packed up the apartment and rode out to Bogotá. In argument, we tag-teamed two different leasing agents. We made connections between traffic and Ronald Reagan. My in-laws invited me to lunch. The sun set as I wasted precious time in a meeting for Brownstone Magazine, an environment I would eagerly leave not even two weeks later. Lulú and I lost time getting shit-faced at a rooftop bar. We headed to the Airbnb, hand-in-hand, and once there downsized my four items of luggage as best we could. We found ourselves distracted and had to speed-run goodbye. Birria in hand, we watched Dreamgirls.

It’s much more than 2007’s most-snubbed film.3 Dreamgirls is what I show everyone I love before I leave places I love. Routinely, I’m in tears by the time Anika Noni Rose, B, and Sharon Leal get to snappin’ and workin’ those shoulders. For months, leading up to my departure, I found myself waving in a elegant, cascading manner, unconscious, in moments of pure happiness. “It’s hard to say good-bye, my love. Hard to see you cry, my love. Hard to open up that door when you're not sure what you're going for.” Shrouded in metallic satin, their velvet harmonies afford goodbyes the glamour of reassurance. (Later, long after I boarded, Lulú would avoid getting robbed in the streets of Bogotá by crying to this same song.)

I showered, slept for 10 minutes, and we headed toward the airport. This final goodbye isn’t dramatic. We confirm, sadly, the existence of my flight. We check my luggage. We exchange my pesos for dollars. We share water and talk about everything that needs to get done that day like we’ll see each other that night.

Edificio Cabrera 85

Wheelchair accessible: Yes

Pet Policy: No fee

Shower Satisfaction: 8/10

Chances of Return: Negibile, as in never

Expense Total: A private car to Bogotá [COP 110,000 / $28] + an overpriced Airbnb [$48] + the Uber from Fontibón to Zona T [COP 30,000 / $8] + enough speciality cocktails to drown in [$48] + my last meal in Colombia [$20] = $152

Cry Count: 3

Chicago, Illinois, United States (Friday)

I’m the youngest person in business class. I’m not the only woman, but I am the only Negro. These facts repeat themselves every time the white man managing to manspread in our spacious suite glares at me for matching his malice.

In the air, I’m numb, slightly hungry. I’ve made it through security and boarding without crying, so why give up now? Sliding on an eyemask, I fold myself in the crevice and sleep. I wake every 30 minutes, agitated even when I’m offered l'omelette or French toast. I live in my camera roll, deleting and conserving as needed, archiving my many chapters.

I think about the last time I had to rent a car, an experience familiar to any member of the extremely poor or the extremely rich. My mother had done her big one and found herself on the streets again. Ever the footsoldier, I received orders of rising with the sun to: drive a rental sedan from San Marcos to Temple, rent a passenger van, clean out my mother’s storage unit, load said rental, drive down to unload in Austin, drive up to Temple, and finally drive my happy ass back to Austin. In layman’s terms, that’s 300 miles (480 kilómetros) and a mountain of therapy invoices.

I hadn’t seen the woman in seven years. Yet there we were, back like we never left, acting out the same old script. It was fucking boring. I trembled behind the wheel when the torture finally ended. The whole way home, in business class, I wonder how much my anxiety had to do with the van.

As the plane descends, I register middle America. To speak of its landscaping, the first word that comes to mind is order. Everywhere, clean cut roads eventually lead to urban centers of varying size. Parched farm land, desperate for rain. Outrageous in contrast, loom lush golf courses, polished to perfection. And then, of course, arrives the false chaos of Suburbia — template houses equally distanced a mere skip away, lined up in neat, curved rows. Above ground, swimming pools shimmer in every other backyard despite Illinois’ below freezing temperature averages. A sudden abundance of Amazon warehouses tells me it’s time to prepare.

We land and the lovely flight attendant who held up boarding to gush over my camera wishes me good shoots. I dash through the airport, concerned that George has not eaten, drunk, or used the bathroom in 12 hours. It’s a smooth ride until customs.

When I approach the podium, a tall man with a greasy goatee and gut appears. He’s holding a customs declaration form. I greet him, expectantly. He stares at me, blankly. Ever so slightly, his upper lip starts to curl. He shakes the brochure in my face. We raise our eyebrows at each other. Finally, he shouts. “I’m showing you what I need!”

There, in the airport, a decade-old memory flashes in my mind. I turned to Carol, aghast. “People do not say hello!” It’s not an American thing, it’s a Midwest thing.4 I learned as much when she dropped me off at Northwestern. This calms me.

I bare my teeth. “Hi, how are you?”

This gets him hot. He grabs a laminated slip of paper, throws it on my luggage, and sends me to the second inspection zone. The detour caused by his temper tantrum takes all of five minutes. In record time, George and I leave the airport.

My stroke of luck is ending and, worse, my patience is wearing thin. I have no idea how to get to the hotel. I can’t take a luggage cart on the elevator which is the only way to get to the free hotel shuttle. I can’t even get a Lyft or Uber because that option also requires changing terminals. I select the only option available — taxi — and pray to God the fare doesn’t bankrupt me.

In the meantime, I sense I have become unmoored. Even though I am clearly struggling with my luggage, I can’t find a single person to fall over themselves rushing to my aid. Back in Colombia, I wouldn’t have to lift a finger in these conditions. And that’s to say nothing of Lulú. Briefly, I remember that I am now Black in North America. Here, I receive overt rejections, basically invisible to everyone who isn’t sexually attracted to me.5 There, I am the best thing at the party. My Blackness was largely valued in Colombia. It didn’t help white Colombians understand my identity as an American, but it did help them understand me. Always, my womanhood foot the bill.

We’re at the hotel in ten minutes. When the taxi driver asks whether I’ll be paying with cash or card, I ask if we can return to the airport.

In the stress of loading the taxi with my two large suitcases, carry-on, and George’s unwieldy carrier, I left my Important Documents folder behind. That Godforsaken luggage cart had me beat. Absent-minded, I lost my driver’s license, two passports, social security card, $500 in cash, all of George's immigration papers, and my only credit. These, the trials and errors of becoming a responsible adult.

Behind the wheel, the Nigerian man with a wide face who reminds me of my father doesn’t charge me for the mistake. Instead, after we get the goods and hop back in the whip, he asks why I’m crying. This is a profuse, embarrassing cry. One born from a frustration of being so stupid and an immense relief that — despite it all — I am blessed and highly favored. And there’s also an acknowledgement.

This happened because my team is incomplete. I’m on my own, and it feels foreign. I miss Lulú, who would’ve grabbed the folder and avoided this chaos without a single word.

“I was worried the folder wouldn’t be there,” I admit. I sound so childish, even worse for the snot running down my lips. The taxi driver jumps to tell me that someone would have to be the dumbest person in the world to steal from a stranger at the airport. “Cameras are everywhere, man! You think they’re not watching? Oh, they’re watching! I tell you ...”

Sure enough, when we arrived, everyone seemed to be in on it. I couldn’t even get a word out before the curbside attendant asked, “Missing your passport?” He ushered me inside like secret service, even ringing alarm with his walkie talkie. In under a minute, the folder, all items intact, is in my hands. I want to get on my knees and praise the panopticon because it has finally worked in my favor.

I tip my taxi driver ten percent. It is not enough, but it’s the highest denomination the app permits.

After check-in — where I have to remind the concierge that I have a cat — I run to Target across the street. Oasis in the middle of the Sahara. As I enter, I get a vague feeling that I’m supposed to be boycotting these four walls. The reason why doesn’t immediately present itself, but I do understand it has to do with my identity as a Black woman.6 Pausing, I consider.

On one hand, I haven’t been a bootlicker since tenth grade. On the other hand, I simply haven’t been in the mix of U.S. politics and culture. My decision comes down to a worry for George. Inside, I spot a Black woman around every corner and feel less nauseous about crossing a picket line.

I’m plagued with an anxiety of overconsumption. It’s innate, the desire I have to buy everything that slightly interests me. A cute denim mini-dress, family-size gushers, raspberry gelato, and a cooler. Hyperfocusing on the cooler, a completely unnecessary expense at this time in my life, helps me lock in. Even limiting myself to the essentials, I end up dropping $70.

My inventory has increased by: 15 pounds of cat litter and three packets of wet food that will go ignored until we arrive at Carol’s; an aluminum tray I pray George can accept until I get her a permanent litter box in Texas; and a charging cable I haven’t seen since. I veer off course here, grabbing one oversized tote to carry all my purchases (sustainability, no?), beef jerky, and kombucha.

If there was ever a culture shock to be had, it’s (re)discovering the price of being an American.

Finally, George is settled in.

I lay on the floor. I still feel nothing, not even hungry. It’s a beautiful Midwest day: wispy clouds cluster around a blazing white sun, lazy against a baby blue sky. Rosemont has nothing to offer except highways and parking lots.

It’s weird and not weird to be home.

The one solace I have in this moment is George, who is playing and running around this hotel room like a toddler on sugar. She’s been a saint throughout this whole travel experience. I consider this insane ‘cause she’s the most misbehaved, feral thing I’ve ever laid eyes on.7 Throughout the entire process, however, she has displayed a particular discernment I’ve never experienced in an animal, much less a cat as demanding as she. I truly feel she understands me when I tell her that we’re on to bigger and better things and that this journey — as tiresome as it will be — is our first step. There’s no other way to put it: my cat understands when it’s time to lock in. She gets that we’re a team.

Finally, I have an emotion not brought on by adrenaline or instinct. I’m grateful. I’m having an adventure with my cat and, so far, I’m not traumatizing her. I suddenly feel an ache: there she is, my heart outside of my body. Many people do not understand me. George does.

A setting sun helps me get a move on. I run across the street again, a beeline for Panda Express. In my hotel room, I devour hot orange chicken, honey walnut shrimp, and lo mein. The Princess Diaries is on.

I feel a nostalgia of cinematic proportions.

I’m a girl again. Chubby cheeked and loud, fielding threats of detention and visits to the principal if I don’t sit still. But they fail to realize I’m bouncing with impatience ‘cause it’s pay day. That means Wal-Mart and Panda Express. It’s the one day the whole month I feel happy.

At the same time, I feel like a very different girl. A fish out of water, on a plane for the first time, really truly on my own in Evanston. I had a second childhood at Northwestern.

When it hits me that — with the migration of my memories to Texas — I will no longer have any connection to Chicago, my eyes burn. I close a chapter all on my own that night. But the truth is that the party ended a long time ago. Clean, moisturized, and full, I go to sleep immediately, terrified of the inevitable.

La Quinta by Wyndham Chicago O'Hare Airport

Wheelchair accessible: Yes

Pet Policy: Cats and dogs accepted, $25 fee

Shower Satisfaction: 6/10

Chances of Return: High

Expense Total: hotel [$146] + the taxi mistake [$46] + George’s boarding [$25] + an obligatory Target run [$75] + a two-entree meal and disappointing bev at Panda Express [$22] = $314

Cry Count: 2

Cincinnati, Ohio, United States (Saturday)

My first day in America begins with a gulp of air at 4 a.m.. I detect a seismic shift in the world. A phantom tug on my elbow pushes me into action. I brush my teeth and wash my face with unnatural speed. There is no sun and there is no moon. Only dark obsidian.

On the television, I watch a program about a man who travels through time to warn everyone that John Wilkes Booth will assassinate the president. I won’t write what I hope the universe is suggesting because I trust you know how to use your imagination.

Down at the front desk, I ask when the next shuttle is. Unsatisfied with the answer, I ask how long it’ll take to get to the airport’s rental center. The concierge lets me know it’s a quick ten-minute Uber, probably less.

When he mentions that it’s about a mile away, I ask, surprised, “Oh, I can walk there, then?”

Even more surprised, he frowns. “I guess.”

Mentally, I add another note to my growing list of how to spot an American. Besides our pudgy arms and noses, you have to consider who is willing to walk, and how far? In my homeland, the threat of 20 minutes on foot immediately warrants an Uber. If I suggested that in Bogotá, I’d get flamed for being gomela until the end of the night. Amused by the irony — in Colombia, I am staunch and uppity and in America, I’m low-class and loud— I start off toward the car rental facility.

I get lost, hopelessly, if only for the fact that the United States is not designed for pedestrian transit. I experience dissociation — a true, stop in my tracks reminder of the dystopia I have returned to — when I pass a Popeyes with a parking lot full of electric car charging stations. It’s an image so incorrect I feel as if I’m dreaming. The last time I was home, the clientele of electric car owners did not intersect with those of Popeyes. Remembering I’m in Rosemont, I calm. I skip across seven lanes of traffic, knowing Lulú would never permit me this simple pleasure even at this before-the-early-bird, nearing-the-end-of-demon-time hour.

A day before, at this very moment, I was singing Dreamgirls in the shower.

Concrete gives way to dewy prairie. A bunny, velvet tan and underfoot, catches my eye as it dashes to safety. I’m reminded of the gerbils we watched scurry into the marsh my last day in Colombia. Yesterday. Overhead, planes soared. Suddenly, I was above it all, looking down on myself, living and leaving at the same time. I hadn’t even checked-in for my flight and already had a double identity to struggle against.

I am up first when I finally reach Avis. David, I believe, helps until he doesn’t, letting me know the vehicle I selected had been sold out since the previous Tuesday. Since I had booked with a third-party — Priceline — Avis never got the reservation and couldn’t plan to have my van available.

I find it baffling and wholly expected.

As directed, I survey all available options. I drive myself mad trying to compare the screenshot of my storage unit with the space offered by these backseats. I settle on a Ford Expedition and return to the office, beating a trio of tatted Mexicans. Pero, like, bien mexicanos. Naturally, I tune into their chisme. The older men, fitted both in caps, at each other’s hips like a couple of señoras, exclusively speak Spanish. They ignore the younger man’s asides, exclusively in English, where he routinely misunderstands the question, giving where instead of when the huracán on the broadcast happened as wondered aloud by the elders. The youth — no older than 16, 32 max — stands separately as they go on, the conversation painful in its physical and idiomatic separation.

I am watching my life play out on a set, fluorescent lighting harsh the same way it is on telenovela sets. Our phones serve as boom mics, listening in, learning how to get us to consume, consume, consume.

In front of me, the white backpacker mother-daughter duo being accused of fraud can’t compete.

Next up, I experience the loveliest interaction with a human being since landing. Juan is portly, mustached, and elderly. I assume he’s Cuban because of his love for salsa, but he tells me he’s born and raised Mexican. The salsa is a relatively new thing. He was a rockero in his day. He tells me about watching Metallica and AC/DC open for The Rolling Stones. He tells me Aragon Ballroom used to be a shack. We lament the swiftness with which Ticketmaster has destroyed concert culture.

I leave the office with confidence. I’m high on the relief of not having to drive a van again and Juan’s vibrant emotional wealth. This confidence proved so strong that even turning the wrong way out of the parking garage and having to conduct an emergency 15-point turn does not waver me. Even though I get lost twice, I consider these lucky detours. I need help learning how to drive again, and the lightness of early morning traffic turns the world, briefly, into a crash course.

I pull into the hotel parking lot, blaring Lemonade, and rush through checkout and breakfast. George is unamused and not afraid to let me know. I text Tommy to let him know I’m running late, unaware I previously factored in the distance between the storage unit and the hotel and have a whole hour to arrive.

Going back and forth with Tommy, I still beat his movers to my unit.

A Dave Bautista type welcomes me in, opening the large garage when he spots me struggling with my code. I absolutely love nice people. I glance at the empty space in my storage unit, once so full, before I head downstairs. Combined, Google Voice tells me I have 100 missed calls and text messages. In the office, I dial one of the numbers. Behind me sounds a bright warble. After retrieving my cartoonishly large box of missing items, Chardae and I wait for Mike.

The three of us trade quips and information about our lives, and they become my partners in crime by the end. I remember I’ve never met a stranger.

I push scales, watercolors, trinkets, and socks on Chardae and Mike the same way my godmother would at her softest. Afterward, I considered the ability versus the need to be generous — pawn off material possessions to those less fortunate. This led me to wealth’s vicious cycle and, as always, Reaganomics. The foundation of our trickle-down economy has never been stronger. It started with COVID-19. Five years later, America leads the globe as a fractured dystopia hurtling toward rock bottom.

The question of furniture presents itself.

We debate driving down to South Side. Chardae calls her friend, brunch-drunk at 10:30am. I consider posting on Facebook Marketplace for a flash sale. I even pitch the Dave Bautista types — for there is a second one I didn’t notice when I arrived. I win over the small one, but he’s not the leader. Eventually, we decide on sacrificing space to save my loveseat: A beautiful paisley of toasted citrus and sea shades.

Cleaning out my storage unit takes no effort on my part and is done quickly, all credit to Chardae. We call it quits as we approach an hour, wishing each other well and parting ways. I want to offer them a ride, but the Expedition is occuppied, filled wall-to-wall with boxes for tenants. George and I peel off, accompanied by Beyoncé’s wails of reconciliation. After a run to 7/11 wherein I potentially help youths commit credit card fraud and field off a flirtatious old wino, we’re on.

Traffic is tiresome, but hindsight tells me it could’ve been much worse for Labor Day weekend. I feel that tug of the elbow again. Despite having no real rush, I have to get to the next place. The real pressure is capitialistic in nature; this rental car is by the day.

I leave the Chicago skyline in the rearview. I am going to the crossroads of America. George acts as passenger captain. Cornfields as far as the eye can see accompany us. Every single flag flies at half mast. A gang of bikers escorts us the whole way. Indianapolis comes and goes, a short stretch dedicated as Kenneth "Babyface" Edmonds Highway, and we cross a bridge to enter Ohio. Briefly, we leave Ohio to cross another bridge — this one a soft butter yellow — to enter Kentucky. Five minutes later, we’re in Ohio again. A simple sign of red, white, and blue welcomes us to the heart of America. We turn into Best Western at the first left.

It’s 5 p.m. and I’ve been driving for six hours. Maybe seven because I lost an hour. Or maybe five?

The concierge and I spot each other. He pauses his series of wild gestures. His friend, seated in a yellow Mazda, sighs relief. “You checking in?” The concierge shouts across the parking lot. He’s a brown man, South Asian, wrinkled and furried. He tosses his cigarette with a grunt. He offers his final warning with a stern finger in the friend’s face. We meet in the lobby. We make limited conversation, and I decide I can trust him with my life for the night.

I enter the hotel room and set up George’s things with prisa. I get locked out. When I return to the concierge, he’s screaming for someone to come back with the car. How dare he sleep with his wife and run off in his vehicle? He hangs up and turns to me, again mild-mannered and empty behind the eyes. He issues a new room key and wishes me a nice stay.

I remember that I am in middle America, where the salt of the earth resides. Real people, in other words. I considered adding this criteria to my growing list. You can tell who is American by how willing they are to divulge their personal information to any Tom, Dick or Harry passing by. Then, I remember that’s not much different from how to spot a Colombian. How many intimate details did I learn in passing about desconocidos? The only difference is that I don’t have to exert myself to understand the chisme here.

Americans are so uniquely insane and the proof is in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Case in point —

I’m returning to my hotel room when I spot a delicate plume of smoke spiraling in the air. Baffled, I follow the grey clouds to their source. It’s a shrub.

I stare down the green foliage, engulfed in flames. The sight is so unnatural and confusing that I immediately understand how it would force Moses to change his entire lifestyle in the name of God. I’m considering the threat level of this divine combustion when a man walking his toy poodle calls out.

“That bush is burning.”

“Yeah.”

“You see that?”

“Yeah, I see that.”

“Burning bush!” This makes me smile. The power of collective consciousness, truly, is unmatched.

“Think it’s gonna go out?”

“I sure hope so!” Whistling, the man shuffles along.

This is another interaction I love. For all our faults, I adore how weird my people are. I get inside and watch a marathon of Malcolm in the Middle as George purrs on my chest. It’s a microdose of American culture. I tell myself I am conducting anthropological research before interacting with the natives.

I shower and rot in the second bed, safe from outside clothes. Hunger helps me spend nearly $50 on a salad from UberEats. I run out of fucks to give ‘cause — bolstered with all my favorite ingredients: greens, real shrimp from the ocean, strawberries, goat cheese, and balsamic vinaigrette — it’s worth it. I’m happy to be home where something so delicious is only a click away. The salad is huge, and I spend an hour picking at it, an Eagles documentary on in the background. I fall asleep in a pitch black cave.

Best Western Clermont

Wheelchair accessible: No

Pet Policy: N/A

Shower Satisfaction: 8/10

Chances of Return: Moderate, as in I would never stay there alone

Expense Total: a rental at Avis [$632] + two youths trained in moving [$130] + road-trip fuel at 7/11 [$19] + that delectable shrimp salad with tip [$44] + hotel [$103] = $928

Cry Count: 0

Nashville, Tennessee, United States (Sunday)

You know you’ve arrived in the South when state troopers start hiding in the shadows. If your eye isn’t trained for that sort of thing, you can also tell by the billboards. Every so often arrive large, obnoxious advertisements for Whataburger, Zaxby’s, and Buc-ee's. Repeated reminders of the best we have to offer: a warm, comforting meal.

Food’s been on my mind since morning when I spent an hour in the dining room. Swear to God, I had every intention to journal. Instead, I indulged in some early riser tea. Behind me, an older woman is reading a thin paperback when a pimple-faced teenager interrupts to sit with her. They discuss the novel’s plot, which runs parallel to experiences she had back in the ‘70s. In front of me sit a table of Vietnam vets. I think of my godfather and how it came to be that these men, still proud to have served this country after all this time, end up in a Best Western in bumfuck Ohio. I wonder how everyone ends up here. To the left of the vets, a severe mother-daughter duo dressed in coastal mourning: long, ruffled linen dresses with cork sandals. They’re silent, wearing oversized sunglasses before sunrise. Three generations of light skins sit at the buffet table on my right.

When the youngest boy — in response to a CBS broadcast relaying Trump’s plans to occupy Chicago with the National Guard — asks who the best president is, the entire room freezes. This ice thaws once his brother poses a different question.

“What’s the president the president of?”

“The United States,” their mother offers.

“Where’s the United States?”

“That’s where we live. It’s our country. You are in the United States.”

“Oh! That’s easy. Abraham Lincoln.”

This starts a lengthy debate between the three boys and scares off the skin-and-bones, sun-dried couple sharing their large table.8 Their debate continues until the mother puts her foot down and says Barack Obama is the best president we’ve ever had. I laugh, clearing my plates. No one has enough sense to respect the late Jimmy Carter.

Reminded of Big Jim, I text Carol a couple of photos. I’ve failed to let her know I landed stateside, much less woke up in Cincinnati. Her reply is immediate. “What are you going to do with the cat?” Well. What does she mean? What am I going to do with the cat that I spent upwards of a thousand dollars to fly overseas? I hoped to introduce her to my daughters.

Carol doesn’t want a cat in her house ‘cause there’s already too much going on. I am driving across the country to live in her house with a cat.

We go back and forth to get to the bottom of this tremendous miscommunication. Simultaneously, I search for boarding services and low-income housing in Austin. We decide to play it by ear which only means Carol’s run out of steam. Dutifully, I pick up her fight to promise I’ll find a temporary home for George as soon as I arrive. She tells me to focus on getting home safely, and we’ll figure it out. I understand this as promising news, but anxiety lingers. Honestly, I’d rather swallow bleach than give up George.

After a mandatory stop at Wal-Mart — my little diva has rejected her aluminum tray and I need gas already — I’m on the road a little before noon.

GPS creates a route through Louisville, and I stop in Elizabethtown to blow bubbles and pee in the woods. For two hours, Lulú keeps me awake, acting as dispatch, sending lunch recommendations. I don’t plan on stopping until I reach Nashville, but keep quiet ‘cause I like her company. From Munfordville, she chooses El Mazatlan Grill even though I’ve emphasized the fact I will not eat Mexican outside of Texas. In Horse Cave, Farmwald’s Dutch Bakery & Deli. Just to bother me, El Mazatlan Bar in Cave City. I sincerely consider stopping in Bowling Green ‘cause there’s Which Which and Chuy’s. There’s also Greek and Thai. And sushi!

I’m hungry, but I resist these urges. I play the same game when I approach Paramore’s hometown: Franklin, Tennessee. This decision is made easier once I learn there’s no mural or statue dedicated to them (flop). I keep trucking on.

And then, I’m in Nashville. It’s 4 p.m., and I’ve been on the road for a little under five hours.

Immediately, the city is thrumming with life. Air rushes in through open windows. Whitney’s got me hoarse, but I’m not the only one. Bumper to bumper on the exitway, a variety of genres pass the ear.

I don’t have the capacity to think, and the valet is kind so I cough up $44 for parking. We check in. I run the routine of bringing in George’s food, toys, and comically large little box, my carry-on full of clothes, and tote full of essentials, with minimal difficulty. I shower and climb into bed. Shortly, George settles on my chest and we watch Mad Money. Her cuddles are expected at this point. I need it as much as she does.

At 5 p.m. I remember I’ve spent two subsequent nights bedrotting. That could fly in small towns like Roseland and Cincinnati, but Nashville calls my name.

I prepare for adventure.

On the elevator, a couple joins me. Dressed in denim, the woman is broad-shouldered and tanned like leather. Her black cowboy boots give her away as a tourist; the smirnoff in her hand suggests she’s from the Midwest. We’re a fan of the paper bag down South. They’re so excited to see me that I wonder whether we’ve met before. She’s obsessed with me and she loves my look,9 and I’m humoring her. Transactional, of course, I fulfill my duty when I’m prompted to compliment her in return. There’s nothing else to do.

Her light-skin boyfriend mentions that he already called her beautiful a hundred times before they left the room. Harshly, I tell him he should’ve done so two hundred times.

We don’t even exchange names before they invite me out. I consider it briefly before learning where they want to go: Post Malone’s bar. They have the nerve to look at me crazy when I ask if he’ll be there. Do I look like someone who would want to spend my only night in Nashville at Post Malone’s bar? I realize that it’s not about how I look, but how quickly I codeswitch in mixed company to eradicate room for mishap.

They’re from Milwaukee and also have a long drive the next morning. We’re going back and forth — them insisting, me dragging my feet — when the elevator lands at the ground floor. Waiting twinks offer their opinion. I should pull an all-nighter with the boozy couple. Nashville is confirmed party central.

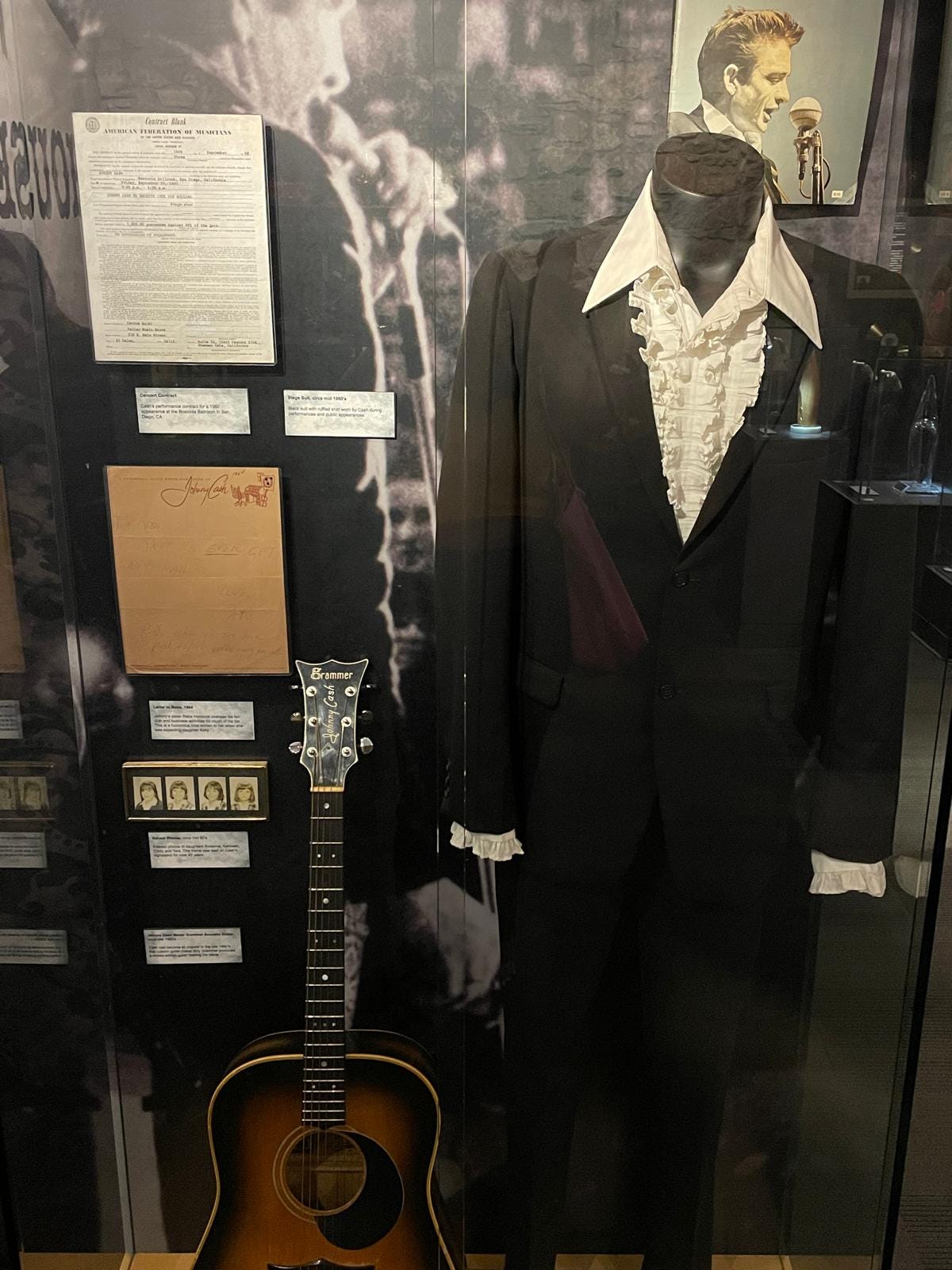

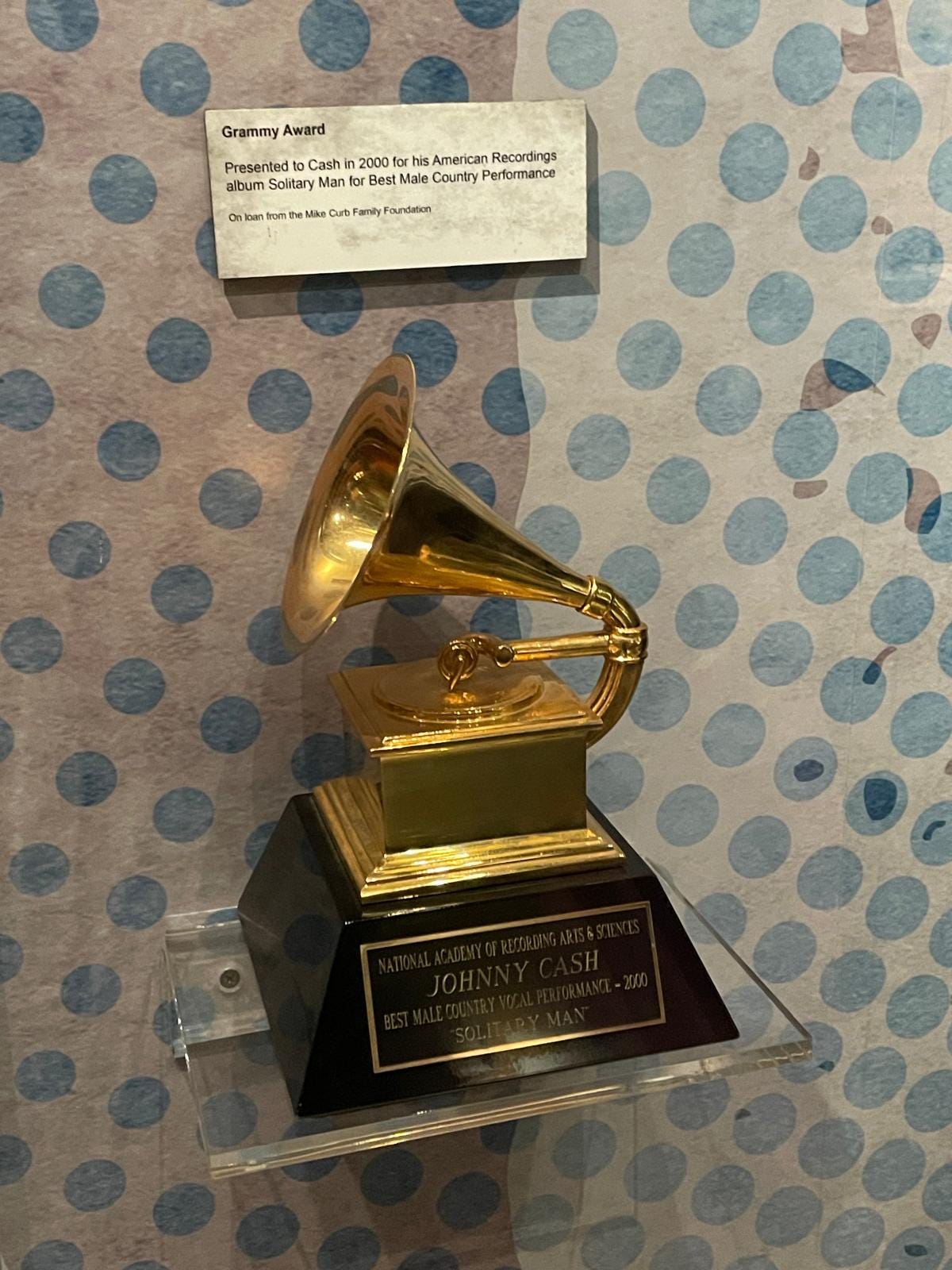

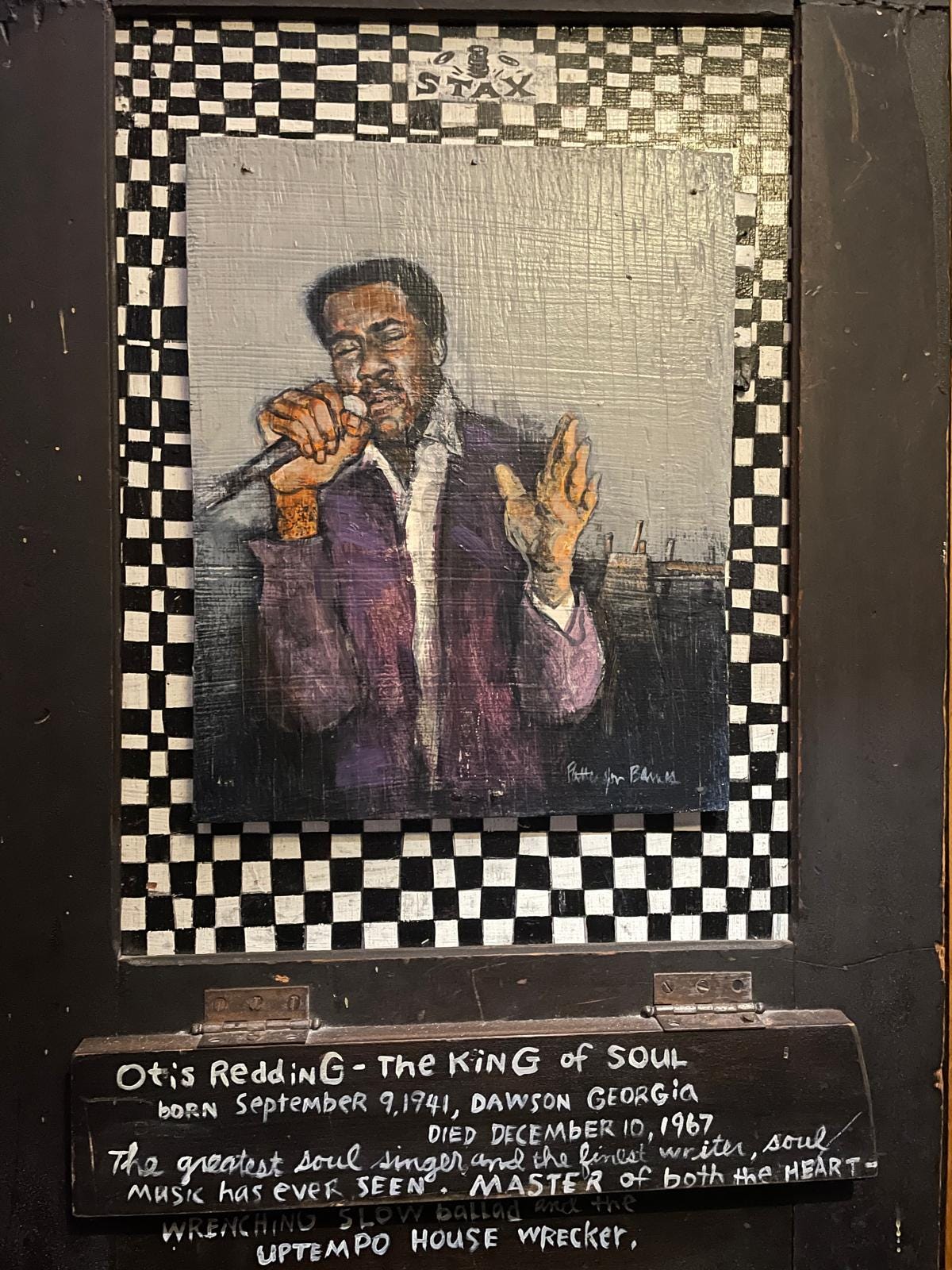

I hop on an electric bike, reminiscent of Paris, and brace the wind as I race toward the Johnny Cash museum. It’s the only curated, culturally-enriching experience available. A golden sun, lemon approaching orange, beats my back. I don’t have many goals tonight: Johnny Cash, Nashville hot chicken, and a park to blow bubbles in. The first thing I notice is how many Black people are in Nashville. The second thing I notice is how drunk everyone is. I race past a golf cart blaring Playboi Carti and advertising Cowboy Karaoke. There’s a hundred pedal pubs featuring patrons of all shades.

In the museum, I start crying. It feels unwieldy to be here alone. I think of my godfather — the reason I studied journalism and the reason I love The Man in Black. Recently, I’ve realized he’s the reason I can hold my own as a music critic. He’ll never get the chance to visit.

And it’s a damn shame because the museum more than deserves its unchallenged three-year run as the best music museum in the country. The kids have optimized it for every kind of Cash fan: music nerds, addicts, history buffs, cinephiles, fashion fanatics, lovers of interior design, etc.. Insistent in its mission to portray Cash as an American institution, the place is thorough. A sharecropper from Dyess, Arkansas, Cash’s loyalty to the impoverished working class started with his picking cotton during the Great Depression. I learn Cash was the first person to learn of Stalin’s death in 1953, and that his first wife was, in some way, Black. His script, scribbled on letters and postcards, is tidy and beautiful. His sentiments are large and expressed freely. I also learn, through the Progression of Sound exhibit, Cash is considered one of a handful of artists to have his music recorded on every media format since the electric era. Further, it’s suggested that he is the only artist to have charted on every format, including digital downloads, while he was living.

Unfortunately, I don’t learn much more. I’m in the middle of observing a photo of Cash with Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Carl Perkins when a man turns around and asks if it’s my first time in the museum. His name is Rafael and we get caught up having a conversation about organizing in Puerto Rico and, generally, how terrible the world is. An attendant arrives and lets us know we have 10 minutes. I dash through the rest of the museum, regretful to lose $15. I hit Lulú back once I see I’ve missed a call and she keeps me company as I dine at Champy’s World Famous Chicken.

I order a Nashville hot chicken sandwich and a high rise. It’s delicious and spicy enough to let me know I’ll regret it later. It’s the perfect night out.

Afterward, I peruse the Walk of Fame park across the street. Of my people, I spot Jimi Hendrix and Little Richard. Infinitely more charming is the amount of families in the park. Children and teenagers cartwheel, somersault, and dash across the small patch of green, challenging their parents’ invincibility. I wish for Lulú. I mosey on, getting lost on foot. I’ve picked up a stray. Several paces behind me on the other side of the road is a stumbling drunk, clearly disoriented. We end up at the Gulch, the fanciest part of Nashville I’ve seen since arriving. The ambience is a complete 180, couples in fancy dress and white-collar families depart and arrive in Teslas.

When my stray crosses the street, I give up on my quest to get home by foot. It’s a challenge I’ve endured more than a couple times in these dataless-three years. I might not have service, but I can learn a place. Better, I know how to find my way home.

I walk until I find an electric bike. (Coincidentally, the path I chose in this new, deviated quest, was indeed the right way to the hotel.) Lurking behind a polished finance bro, I hop on his remains and zoom away. I pass the beautiful statue I met earlier and moon over the way the moon catches perfectly in the circle formed by metal fingers.

Carol sends a text. She’s been thinking about it, and it might be really nice to have a cat in the house.

In bed, George and I watch Big Hero 6. I think of Gattiland, naturally, and how much my life has changed in the decade that I haven’t been there. I think of myself as a teenager, terrified to uproot my life and do this thing called “university.” I remember Allen Drewe, who told me I shouldn’t waste my time by leaving, but they’ll make me manager when things don’t pan out. He said when even though he should’ve said if. I credit his mistake as the reason for my success; people who grew up eating off silver platters simply can’t understand the depths of success achieved out of spite.

Aloft Nashville West End

Wheelchair accessible: Yes

Pet Policy: N/A

Shower Satisfaction: 3/10

Chances of Return: Low to moderate, as in I found it underwhelming for the prices charged

Expense Total: my first Wal-Mart run in three years [$50] + a full tank of gas [$60] + obligatory valet parking [$48] + a Bird bike [$10] + entrance to the Johnny Cash museum on Second Ave [$30] + Nashville hot chicken with tip at Champy’s [$35] + a second Bird bike [$10] + hotel [$121] = $364

Cry Count: 1

Shreveport, Louisiana, United States (Monday)

Today’s my lucky day.

First thing in the morning, I have to teach Lulú the dicho “See a penny, pick it up, all day long you’ll have good luck.” I hesitate when I first see the gleaming copper, obscene against dull charcoal pavement. The thing is, I believe so strongly in the universe I will consider any small inconvenience as a personal affront to my own divinity; the luckiest girl in the world don’t need no penny suggesting otherwise.

Still, I bend down and snatch the shiny one piece right off the street. I hide it near my hip before pulling off.

Luckily, the woman who tries to blow up my spot with a shout of “What a beautiful kitty cat!” doesn’t succeed. Even though I’m obviously pushing a loaded cart with a litter box and the fugitive in question, the front desk attendants only wish me safe travels. I figured that if a hotel could charge paying clientele 50 bucks to park a vehicle, they’d be as eager to charge for an animal that could potentially destroy carpets and furniture. Still, no one suggested I pay for her lodging at check in, and I didn’t want to run the risk of retroactive discovery.

George and I pass Jackson, and I remember how many times I’ve tried to perform the song only to have the plan fall through at the last moment each time. Cash on my mind, I spot a sign for the Tina Turner museum, approaching Brownsville, if only by the grace of God. It’s hidden behind foliage. I debate on stopping, considering the detour a chance to collect another infinity stone of Southern music history. I miss the exit before I can make a decision, and consider it a sign.10

Luckily, I had the foresight to stop in Memphis. Even luckier, I decided on B.B. King’s restaurant on Beale street out of all the options Lulú sent.

In the parking garage, I load George into my tote. I only plan on having lunch and light sightseeing, but it’s too hot to leave her with the windows down. We hike up Beale street to take a picture of the signage. This places me in the clutches of small, independent business owners. The youngest one hustles me with bracelets. They’re genuinely gorgeous and I buy one pink, one purple, gifts for me and Lulú. As I turn to leave, I notice the food truck behind me. It’s, quite literally, rolling loud.

The woman — the girl’s relative, coincidentally — tells me about her daughter as I purchase 5000 milligrams of the presidential blend. She warns they’re strong. I side-eye her.11 She doubles down, insisting, “Girl, I was off one for two whole days.” I raise my eyebrows. We’ll see. When I mention that I’m headed to Shreveport, she tells me her daughter is a first-year law student at LSU. I request a joint and thank her for her service.

After pursuing the empty street, I enter B.B. King's Blues Club. There’s too many white people around for my taste, so I try to get the hostess’ opinion on whether this place has the best barbecue on Beale street. I don’t know whether she really means it or the check is good, but she says yes. I let her guide me to the bar, right in front of the stage. George and I observe warily. Inside B.B’s, Black people are in service. The white woman who waits on me calls me girl and sister and uses other wiggerisms I can’t stand. I’m in the middle of inspecting my plate when the live band takes their place. Four white men and dry ribs. I’ll speak not of the macaroni and cheese. It’s an affront to all that is sacred and I consider swearing off Memphis completely.

In the bathroom, a white woman gushes over George.12 She surprises me when she finally tears her eyes from the cat, nestled in my large, pink tote and meets my eye. Instead, she poses a million questions about how I managed to get her in there. I answer her questions obediently, caught off guard. White people tend to scatter once they realize a Black person owns the animal they are fawning over. She’s so elated, practically over-the-moon, that I have to wonder whether George is the first cat she’s ever met.

I linger near the bathrooms, reading portraits about significant players in Black music history.

The story has changed outside. Music trills in every corner, brash and full of bass. A trio of musicians, high school students, blow Miles Davis on the lawn. Tiny, confident girls steal the show with a faux majorette rehearsal, throwing hips and rolling necks with attitude outside of Alfred’s. At the end of the street, a dance troupe monopolizes the stage to Ciara where I will miss Project Pat’s headlining performance later that night. Police officers peacock at every entrance, constructed, seemingly, while I was in the club. Sunlight winks off their shiny badges.

It’s 901 Day, a celebration of the city’s culture and arts. How is it possible that the first of September and Labor Day and 901 Day all fall on the same day? I marvel at the auspicious alignment like it’s my first day on earth.13

Finally, I feel happy to be home. True glee. I’m practically over the moon. I’m smiling so hard my face hurts. I might cry. It is a blessing to see my people thriving so despite it all. I bear witness to us in community — multiple generations coming together to celebrate a home. It’s a far cry from where they left us after emancipation: no land, title, or family to speak of.

Regretfully, I make my exit. At the gas station, the attendant tells me to be careful twice and I take heed. I can’t stop thinking about the abundance of life in Memphis. Everyone’s a neighbor.

There are fires approaching Little Rock. The image of that white teenager shouting abuse and racial slurs — “Two, four, six, eight! We don't want to integrate!” — behind a resigned but determined Elizabeth Eckford comes to mind. That teenager became a woman, one who allegedly dedicated herself to political activism to course correct, helping unmarried Black women in their transition to motherhood and taking “at-risk” Black teenagers on field trips. And then I think of Ruby Bridges, her little pigtails on her head, held so high. White kids get to inflict pain and be applauded when they change their ways. Black kids have to live with the voice of their tormentors our entire lives.

It’s coming up on 50 years — half a century, no more than two generations — of integration. I’m passing through history, speeding down the memories that are not so ancient! We waited centuries to be free. And we lost it all in 50 years.

An alarm for tire pressure goes off. I don’t know what that means off the cuff, so I pull over and Google. I need air in my tires? I attempt to ignore this, praying the penny will continue to serve me. Ten miles pass before I have a vision of George’s bloody remains scattered across three lanes of traffic. Expeditiously, I make my exit.

Luckily, there’s an AutoZone waiting right there. I’m in and out in ten minutes.

Luckily, I find myself on empty back roads in the last leg of my drive. I’m admiring tall trunks and real, backwoods BBQ joints lining the road when, suddenly, the air changes. Lethargic, but aggressive, sweltering summer air threatens me as an invitation to the swamp. Sure enough, I spot a “Welcome to Louisiana (Bienvenue en Louisiane)” sign mere moments later.

I’ve finally caught a state sign with enough time to pull over — all the more miraculous that I’m not on a four-lane highway. I come to a thunderous halt.

I taste the air. I relent its combative persistence, welcoming it in as demanded. The same fumes vampires of centuries old breathe in. A handful of rednecks stare me down. When I glance at the fading light, strokes of rose and tangerine on a slate canvas, I hop in the expedition and hightail it. I’ve taken care to avoid sundown towns on my long route, but there’s no such thing as being too cautious when returning home.

If Nashville and Memphis were loud, overcrowded, and vibrant, Shreveport is adrift and desolate.

As I near Balley’s Hotel & Casino, dust darkening the sky, I note how little people there are to observe. I feel phantoms in the casino, loud games whizzing and whirring to cover up the sound of them passing through the walls, ascending the elevator. I leave a space for a visitor everywhere I go.

Luckily, the hotel accepts George.

I’ve already checked in and made pleasantries with the wrinkled concierge when, as I’m returning from the open five-story garage with George’s litter box, a slender valet asks if I have a cat. I assume he wants to gush over her so I chirp, “Yes!” His face becomes stern as he informs me that the hotel doesn’t host cats.

Before I can make a run for it, I’m ushered over to the front desk where I will be given a refund. I start crying, immediately, because I can’t imagine having to find another place to stay. It’s 8p.m. and I need a shower.

Another, different concierge gestures for us to approach the counter. The valet stays at my hip like a guard. Before the woman speaks, I present my case: “Listen, I really didn’t know. I checked the website and it said you accepted cats. I’m only here for a night. I’m leaving really, really early in the morning, so we’ll be here for less than 10 hours. We just need to get to Texas. Please, she won’t be a problem, we’ve been traveling for days and she’s perfectly calm and hasn’t destroyed anything. Please, please, don’t make me find another hotel.”

This comes out childish, of course. My voice wobbles and stutters and the dirt on my fingers makes wiping my eyes a lethal decision. “She’s already in the room and everything,” I add.

This stumps the woman. She turns to her colleague with a raised brow. They go back and forth — how could I have checked in with an undetected cat? Finally, the one in charge of resolving the situation holds up a finger. She makes four separate phone calls before returning and saying we can stay. I trip over myself thanking her, profusely. She smiles politely. The valet is pissed. Beside me, a white couple is battling with the white concierge and losing. They move me to the fifth floor — where only dogs are allowed — and I run before they can change their mind.

Luckily, I make it through the night without getting slaughtered. Upon arrival, a skeleton man with a scruffy beard asked for some change. I told him, truthfully, that I had to return to the car. After I checked in, I would pass him something. His impatience led him to follow me into the lobby and nearly up the escalators. He thought I wanted him to come in with me. When I repeated that I would be right back, he said not to worry about it. This hurt my pride for some reason. I hate it when people consider my word worthless. I dropped everything, George included, and fished in my folder of Important Documents for a crisp $50.

My luck continues when the half of gummy I popped after my shower knocks me out. I wake well past midnight, starving and itching to gamble.

I feel shy in the casino, especially when I see three separate gamblers asleep at the wheel, clothes tattered and stained. They remind me of my mother. I leave shortly, and meet the UberEats delivery man. I’m carrying the Taco bell bag to my floor when I spot the scruffy man heading straight into the casino. I avoid his eyes so that my disappointment can’t speak for me. He calls out to me, unabashed. Luckily, I don’t consider it a lost $50. I hope he ate, but it doesn’t matter whether he wastes my generosity at the slots.

This time tomorrow, I will be home, permanently, for the first time in a decade. There will be no plans. There will be no travel ni trabajo. The future is uncertain.

Bally's Shreveport Casino & Hotel

Wheelchair accessible: Yes

Pet Policy: Dogs only, no cats, $50 fee

Shower Satisfaction: 10/10

Chances of Return: High, but without the cat

Expense Total: a McDonald’s breakfast [$11] + garage parking for four hours [$12] + matching bracelets [$20] + a legal drop [$60] + an underwhelming lunch at B.B. King’s whitewashed bar [$26] + a full tank [$65] + gas station snacks and chapstick [$26] + a generous act [$50] + hotel and George’s fee [$145] + late-night Taco Bell [$20] = $435

Cry Count: 2

Austin, Texas, United States (Tuesday)

Everything is sunrise when I wake up. Soft light filters in and I see George, casted in amber and yellow. Auspicious. I leap from bed with luck on my brain.

Another day, the last of my long journey, has begun.

I pull the car around with a quick thanks to God for making it four nights with minimal disaster. I load up, a process so routine and simple at this point I lament I’ll never do it again. George and I dine in the ground floor cafe, where, for the first time, a white woman calls me sweetheart and I am not enraged. I believe her sincerity and further, I trust her.

I nibble on an omelet and hashbrowns and think about what to do with my life. Three years ago, I opted out of the demands on American life. All that momentum — the full-ride scholarship to our country’s premier journalism school; with a two-for-one special, getting a bachelor’s and master’s in four years; and receiving specialized training from some of the smartest music writers around — out the window. Halted, a full stop, by Peace Corps.

When I finish breakfast, it’s 10 a.m.. I’m late. The movers will be there at 3. GPS says I’ll arrive in Austin at 4. I ask Carol to coordinate with them before peeling off.

Lulú’s on the phone, coaching me through crisis.

I want to be a writer. But I already am a writer. I want to be recognized as one. A great one! Is that a crime? And I want to surround myself with other great writers. What profession do I need for that? All of a sudden, I realize that I’m a coward. I know what needs to happen.

When I tell Lulú my idea she says simply, “Desde el segundo de septiembre, nació tu negocio.”

It’s a little after 4, and the closing notes of Homecoming announce my arrival to Westlake. Chuck and Ash help me reverse into the driveway and immediately get down to business. Carol and I, harassed and hurried, eye the car, trying to find George who leapt from her carrier and tucked herself between boxes around lunchtime.

I’ve been terrified I left her at the gas station — that she scurried out of the car when my back was turned. She would never, but I didn’t hear a single meow the whole trip, a huge difference from our first days on the road. Briefly, I entertain the fear she got herself crushed. Carol’s concern is that she’ll leap from the car and disappear in the hills of Westlake. I’m on the verge of having a panic attack when she finally appears, settled in the undercarriage between two cushions. I don’t even have time to cry with relief when Carol suddenly cries, of Ash who she has been signing with this whole time, “He’s from New Orleans!”

The ghosts persist.

I thank Chuck and Ash for their help — unloading takes all of 30 minutes even though I paid for two hours— and rush upstairs to settle in George and wash my face. I have less than an hour to drop the rental at the airport.

Avis is painless. I get lost in my pursuit for Juiceland, forgetful that the store is located behind security. I compare prices for a rideshare home. Rush hour, nothing is arriving for less than $45 and an hour wait. I hop in a taxi and it costs 60 bucks to get home, a drive that used to be 20 minutes before Silicon Valley settled and turned the city to shit.

And now I’m home. It’s over. This impossible thing that I couldn’t imagine doing a week ago proved possible. For the first time in a decade, I’m unemployed and I don’t have a plan.

I try to muster an anxiety about this, some regret that I’ve squandered the one shot I had at being a member of society. But none comes. What does come, is a nauseating paranoia. Rather, a certainty of my peril. I am trapped in the labyrinth. Despite my best efforts, I find myself again caught up in the rat race.

Colombia was an overdue detox from crack water. You know, that same recycled poison, leftovers from Reagan’s reservoir. The thing that infects all my people to value awards and cash over selfhood and community. When you’ve been raised in America your whole life, especially in this digital age, you don’t think to question this innate drive we possess to seize and conquer. Only when you leave, fall in love with something besides the sound of your own voice, can you appreciate life.

They ask what I’ll get up to now that I’m back. One family friend even mentioned that she thought the Peace Corps helped volunteers find employment after service. That’s only for the favorites. Instead, I talk about my garden, all these seeds I’m planting. I dream about what they’ll look like as they grow. I love them when they’re fertilized and I love them when they’re tall stalks. They’ll be beautiful with fresh blooms one day, and I love them just as much when they look like nothing. I’m biding my time, waiting for everything to fall into place as it should.

You won’t find me at a job fair, licking the boot of someone who could care less whether I live or die. I can’t be a cog in this failing machine.

I’m an unemployed bum, technically working full-time as a volunteer household professional. Or rather, a volunteer residential caretaker. Or even, volunteer assistant estate manager. I can’t decide what made-up, white-collar position best describes what it is I spend all my time doing which is probably why I never make it past the first round of interviews despite being wildly capable — overqualified — for everything I’ve applied to. I’m a statistic, only one of 300,000. I wonder how many of those 300,000 are also a part of the 669,000.

So I’m here, being paid in a roof over my head and enough food to feed an army (as is our Italian way) while I watch my godfather’s body decompose, the routine passing of urine and feces his only evidence of life. I watch my godmother not far behind him because of all the stress on her mind, heart, and body. Rising late in the morning, we watch Price Is Right. In the afternoon, Wheel of Fortune. Then it’s time for the five o’clock news. Finally, when the house is quiet with reset, Downton Abbey. On the weekend, I get to come up with ways to educate and distract two precocious children. They remind me how much I love teaching and being a mentor and how little I care for kneeling at the mercy of capitalism.

I’m relearning who I am through the things in my boxes, long lost memories that build me a narrative long lost to me. It’s been three weeks, and I still feel uncomfortable expressing myself in English. My own voice escapes my understanding. When the spotlight is on me and I’m requested to speak Spanish as a party trick, I don’t feel close enough to those asking, stumbling over my words because the reflection of my heart is too fleshy. Tejana down!

If the world was fair, I’d be a learner. Back in the day, philosophy got you paid. I’d read and write and share what I’ve read and wrote with others to help them love reading and writing. I’d watch the sun rise, drinking tea on a wrap-around porch. And I’d write without abandon. And then I’d swim, letting saltwater restart my brain as melodies spill from my lips like swansong heard across the world. I’d spend afternoons creating something important. Or beautiful. Or delicious. I’d entertain in the evenings, sharing marvels of the mind with the masses.

I’d have an open heart. I wouldn’t look at everyone side-ways. I simply wouldn’t have to.

Travis County

Wheelchair accessible: No

Pet Policy: Cats begrudgingly accepted, not allowed on the counters, not allowed to destroy the furniture, not allowed to be loft anywhere unsupervised

Shower Satisfaction: 7/10

Chances of Return: Infinite

Expense Total: a Southern breakfast [$40] + a full tank of gas [$43] + two helpful older men [$110] + enough gas to meet the Avis requirement [$20] a crime to all humanity [$60] = $273

Cry Count: 1

My favorite signs on the road: Malcolm X. Drive, Babyface Highway, Sligo, Kentucky Bourbon Trail, La Grange Historic District, Horse Cave National Museum, Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd (spotted no less than five times), Isaac Hayes Road, Music Highway, Five Broke Girls Cafe, Friendship, Hope, Arkadelphia, Texarkana, Lewisville POP. 915, Magnolia, Spirit of Texas Drive

In total, I spent $2,496 to return to America (not including, of course, international fare for George and I), or roughly 30% of the money Peace Corps gave me to “readjust.” We were $300 over and five cries under budget. Here’s to you, America!

Expert tip: if you can afford it, cancel the ledger in complete with storage units up front because when they inevitably increase the monthly price, it doesn’t affect you.

Delusional and naive, I planned to complete the drive in two days, stopping for a restless five hours in Tulsa, Oklahoma. I fell asleep at the wheel, only nearly avoiding colliding with the shoulder, interrupted an undercover sting operation, and gained five pounds.

The second most-snubbed film of 2007 is, of course, Norbit. Curious how Eddie Murphy is the star of each, but I digress.

Everyone talks about Midwest friendliness, but — speaking from first-hand experience — it has nothing on Southern hospitality.

Keeping in mind the fact I am actively fetishized wherever I go.

To my Black woman readers, please remind me why we’re boycotting Target!

Naturally, everyone comments she’s just like her mother.

I have to admit, I thought they were the white side of the family at first.

(I’m wearing a ratty yellow crop top and black yoga pants.)

The sign is that the West Tennessee Delta Heritage Center & Tina Turner Museum is closed on Labor Day.

Once or twice, I’ve been bamboozled by the same claims in Colombia.

I specify her race because only white people allow animals to distract them from prejudice.

Later, I’ll learn that 901 is Memphis’ area code and the holiday is more than a decade old.

I love it, lo puedo leer varias veces, me encanta como te lleva por cada momento del viaje :3

Thank you for sharing this dispatch, I loved reading it. Wishing you safe travels as you make your way through these 40 cities; I’m looking forward to following along with the next chapter.