[ESSAY] Whose Political Theater Is It Anyways?: Exploitating the Black Dandy at the Met Gala

On the history of the Black dandy, empty gestures, and modern-day Minstrel acts

Unless you’re completely off-the-grid (which, congratulations if true!) you’ve heard of the Met Gala. More specifically, you’ve heard of this year’s theme: “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style,” which uses the Black dandy as its principal muse.

What is Black Dandyism?

First and foremost, I highly recommend Dr. Monica L. Miller’s expert research on the matter in Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity (2009). For its 2025 exhibition, the Costume Institute — which receives donations from Anna Wintour’s fundraising at the annual Met Gala — chose Miller’s text as inspiration. As I understand it, both the theme and exhibition examine the importance of clothing and style to the formation of Black identities in the Trans-Atlantic diaspora.

So what then, you’re asking yourself, is the Black dandy?

Shortly, it’s a nebulous performance of aesthetics with differing goals and achievements based on the century and status occupied by Black bodies in a given era. A more complete answer requires me to return to the 18th century, during the height of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade when African bodies and textiles circulated as commodities within the machinery of colonialization. As trading goods, both represented the exploitation of natural resources by imperial powers.

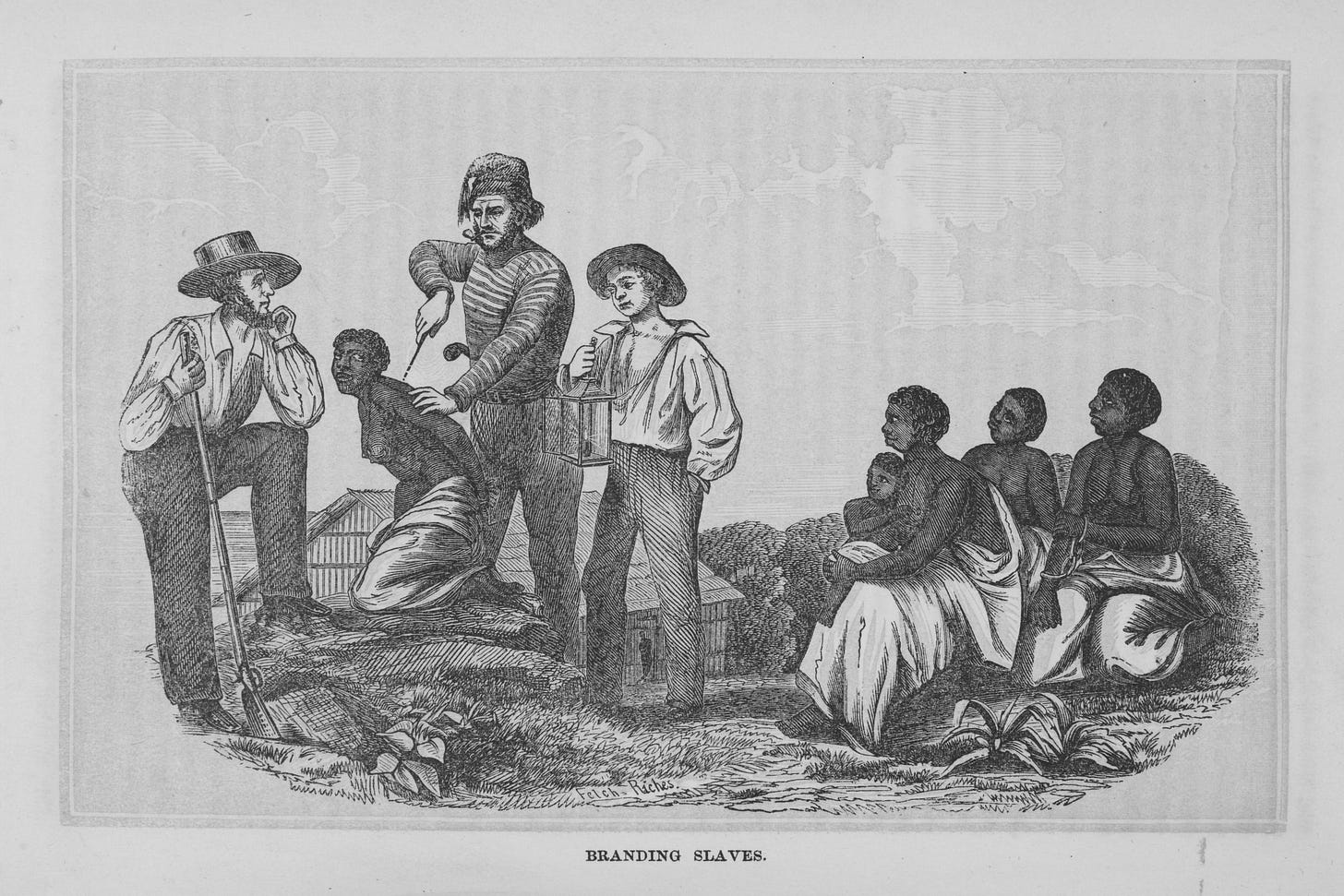

When newly enslaved Africans were forcibly removed from their homelands and stripped of their freedom, they were also stripped of their clothing—symbols of cultural identity. Upon arriving in Europe, they were issued standardized garments designed to erode individualism and establish a homogeneous body of indistinguishable laborers. In contrast, slaves who worked in elite domestic settings received finer garments and fabrics to represent their elevated status. Routinely encouraged by their masters to appear presentable, these “house” or “luxery” slaves came to represent their owner's social capital.

From these conditions emerged the earliest expressions of Black dandyism; What began as imposed performances of upper-class elegance transformed into a chance for rebellion. Both slaves and freed Black peoples started manipulating expectations of dress and behavior, wearing increasingly ostentatious clothing as a means of asserting autonomy. Often, slave catchers received information from masters that slaves had stolen their clothes before running away. Practically, they wore their master’s clothes to protect them in their path to freedom. This performance also blurred the boundaries of race, gender, and class.

Black dandyism challenged the visual codes of white supremacy, complicating the presumed link between whiteness, freedom, and refinement. In short, Black dandyism was a theatrical performance that held aspirations to free Black people from their chains as an enslaved body and also transcend class.

So what did white people do when they saw Black people cosplaying as their free equals? They co-opted it.

In the 19th century, Black dandyism entered the popular lexicon in the form of minstrel shows. These performances often portrayed the Black dandy as simultaneously ridiculous and threatening: a figure of exaggerated vanity and misplaced ambition. The fear expressed by these white actors in Blackface was that the Black dandy was a social hazard. These performances represented common apprehensions that the Black dandy would steal away white women and jumpstart a new era of miscegenation, further diluting America’s pure white race. The anxiety was not that Black people acted as white people, but rather that we could replace them as the superior racial identity. To white people, Black dandyism exposed their greatest worry: the social mobility of Black men as they entered spaces of power and desirability.

The Black dandy became a battleground of symbols. He represented Black aspiration, but also the threat of Black transcendence. To white audiences, he was a harbinger of social equality and white infirmity. In these minstrel shows, the ridicule heaped upon the Black dandy was never about fashion. It represented control.

Today, what we understand and associate with the Black dandy is its 20th century iteration, reclaimed by actors of the Harlem renaissance showing off to themselves for themselves. For the first time, Black cultural expression flourished on its own terms, in a space defined by Black artists, intellectuals, and queer communities. Harlem’s drag balls—extravagant events blending fashion, performance, and subversion—offered a stage for Black queer and gender non-conforming individuals to reimagine themselves through self-fashioning. This birthed Black America’s modern identity.

Important to note in all of this is while Black people are creating a utopia in closed communities, the moment they leave said communities they are acted upon with violence. During the 1940s, zoot suits were considered dangerous. Their flamboyant style and precise tailoring attracted so much attention that white mobs attacked Black and Mexican men for being hyper-visible and unpatriotic (the manufacturing of wool was reserved for soldiers as the United States shipped them off in loads during World War II).

The Black dandy himself enters the literary canon in W.E.B. Du Bois’ 1903 collection The Souls of Black Folk with sketches of educated, refined Black men navigating America’s white supremacist society. Later, in his 1928 novel Dark Princess, Du Bois introduces Matthew Townes, a politically-awakened Black medical student who represents the Black dandy’s diasporic cosmopolitanism. Du Bois used Townes as a symbol of transformative cultural potential, describing him and other Black strivers as “co-workers of the kingdom of culture.” For Du Bois, the Black dandy was not only a fashionable subject, but a figure with intellectual agency, transnational solidarity, and political ambition. In short, the Black dandy represented what it meant to move through the world both burdened by and in defiance of expectations imposed by race and class.

So then, the Black dandy is not a static concept with a singular message or meaning. Highly dependent on context, Black dandyism is a concept that started as a matter of ownership and evolved into a matter of respectability. Black dandyism is a vehicle of class critique, more specifically the assumptions of an enslaved people versus a freed people. Black dandyism is political theater, if not one of its earliest acts. Today, we have to ask ourselves: What form does the Black dandy take? What gesture does he make? What are his ambitions? What does he want to make known to us? Who does he serve?

From Protester to Puppet

There seems to be some confusion on whether this year’s Met Gala theme represented cultural appreciation or appropriation. To put the record straight, it’s neither and something much worse: co-option and exploitation.

As an institution, the Met Gala has fundraised for its Costume Institute since 1948. Then, it was not the celebrity circus we know today. The first Met Gala hosted by Anna Wintor took place in 1995. In the two decades since Wintour has been chairwoman, there have been twelve Black co-chairs, an average of about one per cohort since 2016. Adding this year’s staggering sweep of five — Colman Domingo, Lewis Hamilton, A$AP Rocky, Pharrell Williams, and Lebron James — the total of Black co-chairs at the Met Gala is seventeen. That’s roughly 18%. For Latino and/or hispanic celebrities, that number drops down to 6%.

So for an institution clearly devoted to upholding and maintaining white identity as the fashion status quo, why was it so Black this year? Further, why was that Blackness channeled through the politically-loaded theme of Black dandyism?

Co-curated by Andrew Bolton, the Costume Institute's head curator, and the aforementioned Dr. Monica L. Miller, this year’s spectacle screams diversity. Repeatedly, the team behind the Met Gala slaps you upside the head with ideas of intentionality and equity and representation and all the other filler words that pretend at but do not equal progress. It’s a farce. One so clearly transparent to anyone paying attention, Black or not.

Do you remember André Leon Talley? The fashion journalist who spent his career championing Black designers and runway models, bringing our talent into white spaces? Vogue’s first Black creative director? Mentor to Naomi Campell and stylist to Michelle Obama? The titan of style who grew up in North Carolina during Jim Crow before clawing his way to the top?

There on his sanctified perch, he often found himself sitting beside Wintour. They were friends. Wintour invited Talley to her wedding and even staged an intervention to help him with an eating disorder. For decades, Talley considered Wintour the most important woman in his life.

In an editor’s letter dated April 16, 2025, Wintour wrote:

That was what made André so incredible: his instinct for self-presentation. He understood that, especially as a Black man, what you wore told a story about you, about your history, about self-respect. And so, for André, getting dressed was an act of autobiography, and also mischief and fantasy, and so much else at once. The suit fits him beautifully, by the way. No wonder The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute has included it in the exhibition ‘Superfine: Tailoring Black Style.’ ... André knew who he was, and I know how much he would have adored ‘Superfine,’ every aspect of it: the planning, the press conferences, an issue of Vogue dedicated to it, the exhibition catalog, how many outfits he would have planned for the parties to come ... André was a dandy among dandies and he radiated joy. ... I'll be thinking of him on the night of the Met Gala, an evening made for him—and one I can scarcely believe he will miss.

Though he had been a fixture at the fundraiser since 1974, Talley received notice that Vogue had no need for him to conduct red-carpet interviews at the 2018 Met Gala. In 2020’s The Chiffon Trenches: A Memoir, Talley described the incident as a “stone-cold business decision” and that Wintour “should have had the decency and kindness to call me or send me an email saying: ‘Andre, I think we have had a wonderful run with your interviews, but we are going to try something new.’” Wintour continued to whittle down Talley’s connections to Vogue until he was essentially shut-out from the business. In the same memoir, Talley shared that he felt exploited as an exotic figure and ambassador for a Black milieu within the fashion industry. Despite his contributions to Vogue, he often felt like an outsider, stating that he was "always the first to be bumped from a guest list." These experiences left him with "huge emotional and psychological scars."

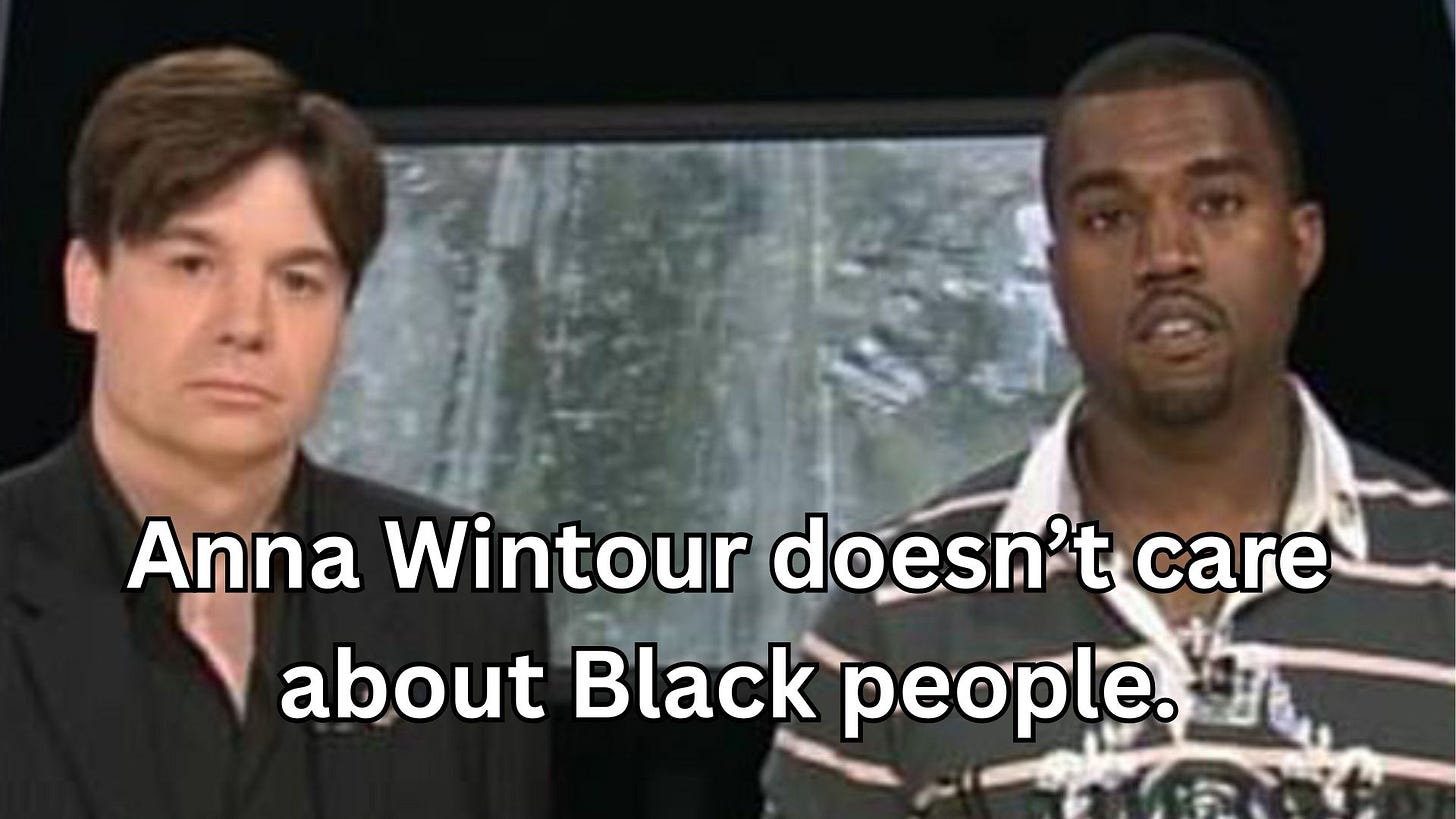

In a 2020 interview with Sandra Bernhard of SiriusXM's Sandyland, Talley criticized Wintour's internal email to Vogue staff addressing the magazine's lack of diversity with: "Dame Anna Wintour is a colonial broad. She’s a colonial Dame… she’s part of an environment of colonialism. She is entitled and I do not think she will ever let anything get in the way of her white privilege."

Talley spent more than four decades in Paris’ front row. A true Black dandy, he died in 2022. And after dismissing him without a second thought, Wintour brazenly exploited his image. On May 5, Wintour enlisted an entire sector of celebrity to invoke Talley’s memory and essentially parade his corpse across the steps of the Met.

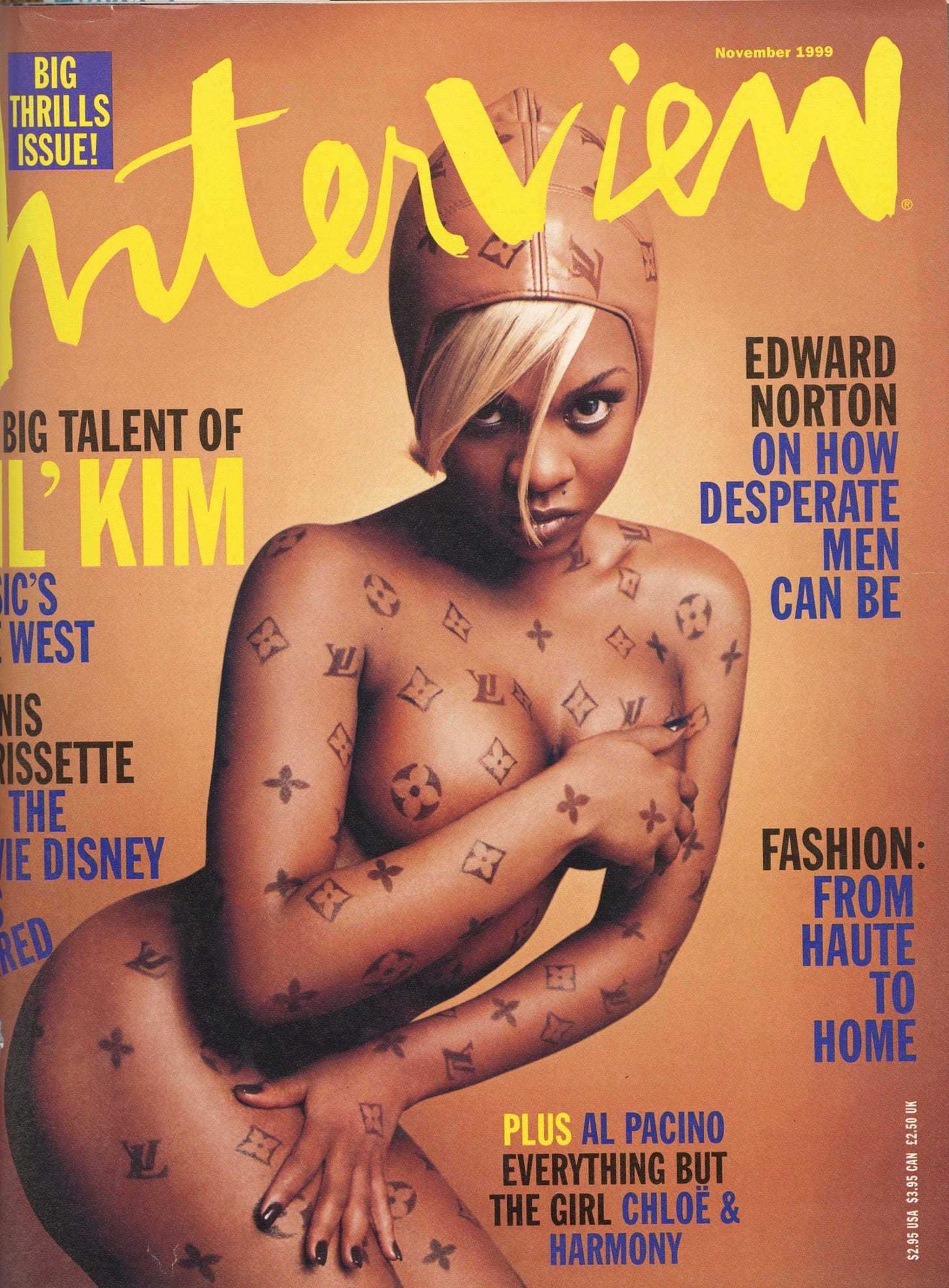

The disconnect between personal politic and public performance has never been so clear at the Met Gala. For the most part, the designers behind this “revolutionary” theme remained the same top luxury brands: Marc Jacobs, Thom Browne, Louis Vuitton, etc.. Though Louis Vuitton provided several looks for the red carpet, only one model had their logo branded into her skin: Doechii. Compared to the last time Louis Vuitton felt the need to adorn a dark-skinned Black female rapper with their logo — Lil Kim for a 1999 cover of Interview Magazine — the difference is telling.

Remember that branding was a routine practice during slavery. To punish runaway slaves, masters would place iron in the fire until burning hot and then press it against skin already worn by harsh climates, whippings, and malnutrition. It was not uncommon for masters to brand their slaves preemptively, claiming ownership of their property the same way they would cattle.

I don’t care much for who came up with the idea or what their intent was or that a Black makeup artist created the prosthetic prop. Historically, there’s only one message: Louis Vuitton has found a slave in Doechii.

The constant Instagram ads of Doechii posing with luggage and accessories wasn’t enough to satisfy a partnership between an artist rapidly ascending to superstardom and a well-established, global fashion brand. She needed to be branded. On a night where Black culture and Black fashion history supposedly reign supreme, a dark-skinned Black woman had a European logo branded on her face. And what really takes it home? Doechii was the only Louis Vuitton model to sport a basic off-the-rack look.

Out of more than 300 celebrity models, only 12 Black designers had looks represented on the carpet. To name some of the lucky few: Christopher John Rogers, Torishéju, Ahluwalia, Bianca Saunders, Paul Tazewell, and a personal favorite for me, Adebayo Oke-Lawal, the Nigerian genius behind Brian Tyree Henry’s gorgeous suit.

Tahirah Hairston of The Cut reports:

“But independent Black designers are still consistently denied the same recognition, resources, and institutional support as their white counterparts. Heritage fashion houses are still overwhelmingly led by white men, and the industry’s gatekeepers — stylists, publicists, and fashion editors — have long prioritized familiar names over emerging Black talent ... That means that the exhibit will be full of Black designers, but, for the first time in the Met Gala’s history, so will the red carpet.”

Once again, the history-making number of Black designers represented at the Met Gala was 12.

And it shows. For a theme dedicated to a style characterized by vibrant colors, extravagant accessories, and gaudy, flamboyant pieces, white, black, grey, and silver dominated the red carpet. To a lesser extent, beige and maroon. There was little texture, little interaction. No fun. The aesthetics simply did not match. Even with such an expressive Black style as inspiration, the Met Gala remained steadfast to an allegiance to the sterility of whiteness.

Choosing Black dandyism as a theme is an overcorrection of Wintour’s long-reported, strategic denial of Black contributions to fashion history. Once again, institutions of capitalism are commodifying Black culture for profit — whether economic or cultural — and enlisting Black agents of capitalism to do so.

At one Met Gala afterparty, celebrity stylist Law Roach was heard shouting, “They done fucked up and made the Met Black,” to which everyone in attendance roared and appaluded. But what was achieved? White celebrities largely failed to understand the theme and shared an uniform ignorance regarding the historical importance of Black dandyism. Black celebrities interpreted the theme as a general win for Black representation and ran with whatever context they wanted to ascribe to it.

The Black bourgeoisie fell for an age-old trick on May 5. “I am here because I worked hard. I made it. I am equal.” Full of delusion and representation politics, they want to trick the Black proletariat into believing the same thing: “Pull yourself up by your bootstraps and this too can happen to you. Dear Negro, don’t you see? You too can be accepted by polite white society like I if you work hard enough.”

The 2025 Met Gala raised $31 million, the biggest gross in the event’s 77-year history, according to Jesse McKinley reporting for The New York Times. It’s an unprecedented amount. Today when people are dying because they can’t afford insulin and ending up on the street because they can’t afford rent, it’s insulting. What do you mean I should appreciate watching “my people” on the steps of The Met hemorrhaging money because they’re cosplaying slaves?

Modern-Day Minstrel Shows

Unfortunately, I’ve arrived at the Sabrina Carpenter of it all. I want to state, vehemently, that as a huge fan I do find it tragic to use her as a vehicle for explaining modern-day minstrel acts, but it is what it is. (Important: Carpenter is not the only celebrity who unwittingly participated in modern-day minstrelsy at this year’s Met Gala nor is she the only one who frequently opts-in to said performances. Consider Billie Eilish, Eminem, the Kardashian Klan.)

An industry veteran of a decade, Carpenter achieved her big breakthrough on the main pop girl stage once she figured out how to package her product. Before today’s sexy Brigette Bardot iteration of Carpenter, we had a mild-mannered Christian girl, angsty grunge teenager, elegant businesswoman, and shades in between. Finally, Carpenter, as any other major-label artist worth a damn, understands her audience.

She knows she has white fans. And she knows she has Black fans. She also knows that their tastes don’t necessarily coincide. Sprinting down the same lane as her musical predecessor Ariana Grande, Carpenter knows how to code-switch. Further, she knows how to profit off code-switching. Whether it's explicitly understood by her and her team, Carpenter knows what to wear, what to say, and what to sing depending on who she wants to reach. Look at how she’s styled.

The photo on the left features Carpenter at the 2024 Met Gala which had a theme of “Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion" and a dress code of "The Garden of Time." Her skin is fair, and her blue eyes are brightened with a complimentary baby blue and white eyeshadow. A peach blush and neutral lip bring everything together for a soft, innocent doe-like demeanor. The kind that is immediately ascribed to white girls no matter class or status.

The photo on the right features Carpenter at this year’s Met Gala. Most prominent is the bronzed, tan skin her styling team chose for her. Then there’s the clear emphasis of Carpenter’s breasts. This paired with the choice made by stylist Pharrell to have her go pantless (a huge difference from the long, full skirt she wore last year), speaks to a desire to give Carpenter a fuller, more feminine figure. Her features are noticeably darker and sexier, the sharp nose contour a dead giveaway.

For Carpenter, one of the first elite spaces to establish a demand for her whiteness has now rejected it. This year’s Met Gala theme allowed and encouraged her to participate in modern-day minstrelsy. Determined by the rules of the institution surrounding her, Carpenter’s social wealth and cultural capital have been awarded instead of penalized because she embodied Blackness.

For those quick to dismiss this critique as trivial or petty, remember that the same “undesirable” features on Black women are often considered attractive when co-opted by white women. Take the “clean girl” aesthetic: slick-back buns, large gold hoops, glossy lips, minimal makeup. That used to be ghetto when Black girls and Latinas in the Bronx sported it. These days it’s not hard to find white women rocking boho knotless braids, bonnets, or long acrylics with noisy gems and accessories. Historically, what is stylistically natural to us because we have cultivated it for centuries is belittled and declared “unprofessional” or “thuggish” until another cultural identity steals it for their use.

The problem proves that because we have normalized the violences committed by culture vultures so much, it’s trite to get upset.

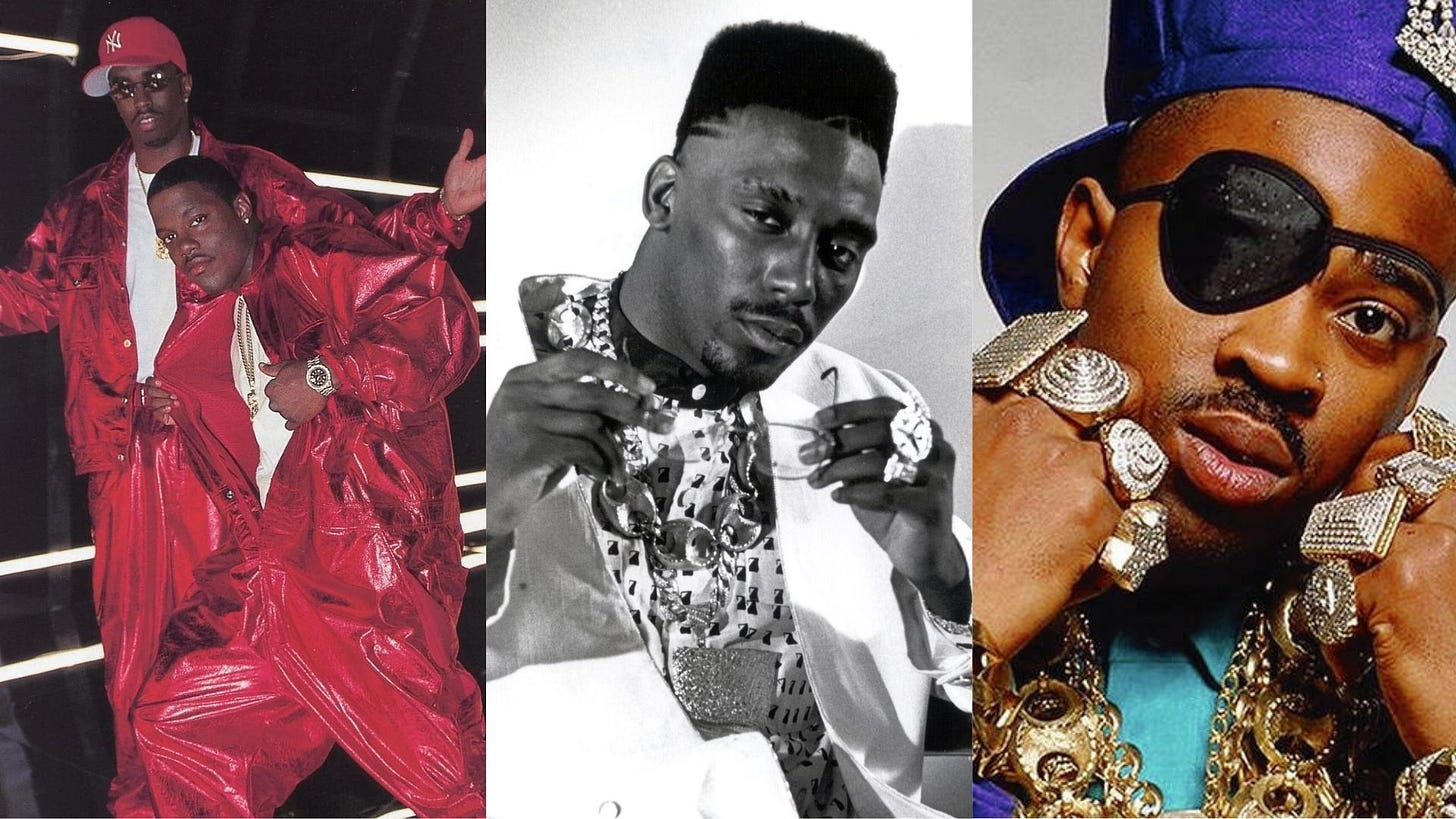

As a vehicle for political protest when we are confined and restricted by white society, hip-hop culture replaced dandyism. Starting with Little Richard and James Brown's influence, hip-hop’s understanding of dandyism also began theatrical: what an audience could see and consume. However hip-hop didn’t embody dandyism in its traditional Eurocentric form but rather remixed it with custom gold chains and logos.

Consider hip-hop’s Shiny Suit days as led by the braggadocious Hype Williams and Bad Boy Records. Suddenly rap was no longer gritty or local or even an authentic form of storytelling and community building. Now it was this glossy, luxury pastime. Their ability to platform hip-hop as a commercial product and cross over into white homes led to the eventuality of hip-hop as indistinguishable from pop culture. This year’s Met Gala revealed that not only did the fashion elite finally catch up to this fact, but they also figured out how to exploit it.

Music became a business and artists became products. More specifically, their style and behavior became commodoties. Excess and controversy became the machine’s bread and butter. Today, this symbiotic relationship is well-established and indeed best represented with the Met Gala. Celebrities don’t pay to go. They are selected by a fashion brand who purchases a table to remain in Wintour’s good graces. Those brands dress up celebrities to impress Wintour and ensure their cultural wealth and economic longevity. Every single celebrity on that red carpet was a pawn. This is the case every year, but I find it particularly sinister that Black celebrities happily became puppets for white fashion moguls in the name of representation.

Who Is All This Political Theater For?

Before we have even made it to the six-month mark of Donald Trump’s second presidential administration, I’m reminded of what Ms. Toni Morrison observed during his first. In her 2016 essay, “Making America White Again,” she writes:

“Under slave laws, the necessity for color rankings was obvious, but in America today, post-civil-rights legislation, white people’s conviction of their natural superiority is being lost. Rapidly lost. There are “people of color” everywhere, threatening to erase this long-understood definition of America. And what then? Another black President? A predominantly black Senate? Three black Supreme Court Justices? The threat is frightening.

“In order to limit the possibility of this untenable change, and restore whiteness to its former status as a marker of national identity, a number of white Americans are sacrificing themselves. They have begun to do things they clearly don’t really want to be doing, and, to do so, they are (1) abandoning their sense of human dignity and (2) risking the appearance of cowardice. Much as they may hate their behavior, and know full well how craven it is, they are willing to kill small children attending Sunday school and slaughter churchgoers who invite a white boy to pray. Embarrassing as the obvious display of cowardice must be, they are willing to set fire to churches, and to start firing in them while the members are at prayer. And, shameful as such demonstrations of weakness are, they are willing to shoot black children in the street.”

Emotionally, white people are themselves inhabiting the spirit of the dandy. They want to disrupt the rapid ascent of Black cultural capital. They hate to see us as equals. It breaks their heart to know that despite generations of strategic torture, we have thrived. But their protest has nothing to do with fashion nor aesthetic. Instead, they protest with violence. They lie on our children: our boys are “thugs” and our girls are “fast” so that’s why they get to hurt them the way they do. They burn our places of worship. They craft intricate rope necklaces to hang us up in trees. They use their good credit and inheritances to force us out of the apartments they once abandoned because it was gettin’ to be too many of us around. They push us out onto crack-infested streets. They lock us up when we take the only options left to us. They put us back on the field, and here we are, picking cotton once again. These white dandies will do anything to hold on to the good ol’ days.

So I ask, who is this political theater for?

When a Black person steps into Black dandyism, they position themselves in a long line of Black history. They continue a legacy of rebellion and protest. When a Black celebrity who has already transcended the class barriers that Black dandyism raged against steps on the Met Gala’s red carpet, they allow themselves to become pawns. They act as evidence that the historically racist institution is not so racist anymore! Whatever act of rebellion they gesture toward is usurped by the increase of wealth held by the white billionaires that plotted to get them there. It is the same exploitative control that football team owners and record label executives have over their players and artists. When a white celebrity steps into Black dandyism, it is a reminder that our culture will never be ours for there is always someone prepared to steal and benefit from it more than we can.

I have to end with Susan Sontag. In 1977’s On Photography, she writes,

"Photography implies that we know about the world if we accept it as the camera records it. But this is the opposite of understanding, which starts from not accepting the world as it looks. All possibility of understanding is rooted in the ability to say no. Strictly speaking, one never understands anything from a photograph….the camera’s rendering of reality must always hide more than it discloses. ... To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed.”

In other words, images allow their viewers to ascribe whatever meaning they want and erase the original intent or moment. Today, when the working class is constantly being sold products and lifestyles we can’t afford, remaining critical of the images we consume is crucial. The Met Gala stripped Black dandyism of a long-storied context and flattened it into an elite spectacle.

What actionable progress — advancement for Black lives and protection of Black culture — will these actions generate? Will cops stop killing Black boys? Will Black people stop dying during childbirth? Will the courts stop locking Black people up at exorbitant rates? Will, in 2025, Black people stop getting lynched? Doubt it. But I do one thing. Anna Wintour doesn’t care about anything that affects Black people materially, and this year’s Met Gala was a new-age hatecrime.

VERY interesting article!

A couple of things to add: in the 18th Century, clothing codes were enacted as part of the clampdown driven by the Stono Rebellion in 1739. Even though fabric and colour was codified, enslaved Africans found ways of personalising their clothing (especially in South Carolina).

"Favoured" slaves, whether house slaves or artisan slaves, were sometimes given gifts of their owners' cast off clothing.

Free Blacks also flouted the clothing laws.